On January 31, 2025, Mr. Donald Trump ordered the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to release millions of gallons of water from Northern California dams in what Trump argued was his way of helping to stop the fires in the Los Angeles area and also help farmers. This resulted in 2.2 billion gallons of water flowing out of reservoirs.

Trump consequently posted photos on his social media site, Truth Social, showing rivers flowing with lots of water, claiming he saved the people in L.A. He also took credit for the fact that around that time there was some rainfall in the area that helped douse the fires.

Trump blamed the fire devastation on poor water management in California, including conservation policies to save endangered fish.

That’s not true, Mr. Trump. And no, you did not save Southern California by dumping billions of gallons of water onto Northern California soil.

So, how did it come to this? Let’s start with the fire, and then I will take you on a quick trip to explain how recent events highlight the need for California to take full control of its own water resources.

The Fire

After eight months of zero precipitation in the Los Angeles Basin, the National Weather Service issued a warning when the Santa Ana winds began to gust at speeds of up to 100 miles per hour in some regions. Combined with a landscape carpeted with what was basically dried tinder, this made for a dangerous recipe ripe for incendiary explosion.

On January 7, the beginnings of the Palisades Fire near San Diego were spotted by UC San Diego’s AlertFire program. Later that afternoon, the Eaton Fire flickered to life near Altadena. The next day, wind gusts of 100 mph are reported in the San Gabriel Mountains, and three more fires erupt: the Woodley Fire in Sepulveda Basin, the Sunset Fire near Hollywood, and the Lidia Fire near Acton. Governor Newsom sends in 1,400 firefighters, air and drinking water alerts are issued in Pasadena, and President Biden declares a major disaster alert.

On January 9, Governor Newsom activated the California National Guard and the Kenneth Fire in West Hills is spotted while the relatively modest Hollywood Fire is 100% contained. The next day, the Archer Fire is reported in Granada Hills.

It is by this time, January 10, that so much acreage is burning that there are reports of low hydrant pressure in neighborhoods that are affected. About 20% of area hydrants ran out of water. The Pacific Palisades reservoir, which had been full, was nearly dry, and water was unavailable from the San Ynez reservoir because it was undergoing maintenance at the time.

Meanwhile, while Mr. Trump was denying aid to California unless we agreed to his political demands, Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada sent fire crews, helicopters, and equipment to the scene, and Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo also pledged to send fire fighters.

Thankfully, with a bit of help from a long-awaited rain shower, the fires were finally 100% contained by January 31.

The fires, especially the Palisades and Eaton Fires, continued to blaze for the rest of the month. In the end, 47,900 acres had burned, 16,250 structures, including homes, businesses, and schools, had been destroyed (historical buildings such as the Zane Grey Estate and the Andrew McNally house are lost forever), and 29 people had died. According to a UCLA study, total economic losses are as much as $164 billion.

Who—Or What—Is to Blame?

What caused the fires and all this destruction? And why were they so difficult to douse?

As of the time of this article, the exact causes are still under investigation. However, as I mentioned above, there was dry vegetation everywhere, and the powerful Santa Ana winds fanned the flames into an inferno. There has been some speculation that faulty Southern California Edison equipment might have sparked the Hurst Fire, or perhaps hikers started a blaze with a carelessly discarded cigarette. Almost anything could have sparked the blazes at that point.

Fighting the fires was problematic because of the fierce winds. Yes, the Pacific Palisades reservoir went dry and the San Ynez reservoir was not available, but the problem was not an overall lack of water. Time magazine reported:

Janisse Quiñones, head of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, said later at a news conference that 3 million gallons of water were available when the Palisades fire started but the demand was four times greater than “we’ve ever seen in the system.”

About 40% of water used by the greater Los Angeles area comes from Northern California sources. Mr. Trump—apparently under the impression that there is a giant faucet located, perhaps, near Sacramento that the governor can turn on and off—proclaimed on January 27 that he had sent the Army Corps of Engineers to turn the water back on. Trump, as reported by ABC News, lashed out at the governor:

Governor Gavin Newscum refused to sign the water restoration declaration put before him that would have allowed millions of gallons of water, from excess rain and snow melt from the North, to flow daily into many parts of California, including the areas that are currently burning in a virtually apocalyptic way.

As Governor Newsom clarified, though, in a post on X: “There is no such document as the water restoration declaration—that is pure fiction.”

Trump also blamed California conservation efforts to save endangered species such as the Delta smelt for the lack of water. The smelt live in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta between San Francisco and Sacramento, and the California Aqueduct (operated by the DWR) begins near there and eventually leads to Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and San Bernardino. However, conservation efforts involving the smelt is largely a policy affecting farmers in the north. Trump’s accusation betrays a gross lack of understanding as to why the smelt are important—that is, the Delta smelt are a key species that, if allowed to go extinct, would set off a domino effect that would endanger many other species of animals and plants. Furthermore, the state is obligated to do what it can regarding water conservation as defined by the National Environmental Quality Act, the California Endangered Species Act, and the California Environmental Quality Act, all of which became law in 1970.

On January 23, Trump demanded California make concessions before he would send help to the fire-stricken region. He demanded the state change its voting laws and that it immediately release water from dams in the north.

As posted on Truth Social by Trump on January 27:

The United States Military just entered the Great State of California and, under Emergency Powers, TURNED ON THE WATER flowing abundantly from the Pacific Northwest, and beyond. The days of putting a Fake Environmental argument, over the PEOPLE, are OVER. Enjoy the water, California!!!

The next day, the California Department of Water Resources posted on X:

The military did not enter California. The federal government restarted federal water pumps after they were offline for maintenance for three days. State water supplies in Southern California remain plentiful.

The Flood

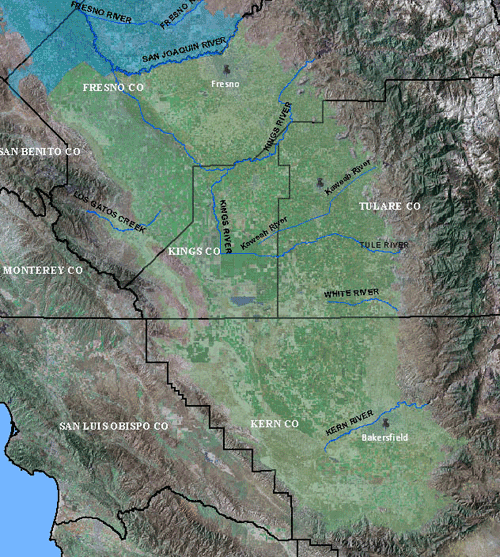

Trump persisted that he could fix a problem that didn’t exist. So, on January 31, he did have the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers release water from two dams: the Terminus Dam at Lake Kaweah and the Schafer Dam at Lake Success, dams that are under the management of the Federal Bureau of Reclamation and not the DWR.

The water in these reservoirs is stored to help irrigate farms in the Central Valley in the dry summer months. Instead, 2.2 billion gallons of water were drained. As a result, Lake Success went from 20% full to 18% and Lake Kaweah went from 21% full to 19%.

The two rivers below these dams (the Kaweah and the Tule) don’t flow to Southern California, they flow into the middle of the Tulare basin, where the water simply leaches into the ground.

(Los Angeles is not pictured on this map because it is about 100 miles to the south, on the other side of two mountain ranges.)

Letitia Grenier, director of the Public Policy Institute of California’s Water Policy Center, was quoted on the California governor’s website: “The transfer of water from Northern California to Southern California is not related to water availability to fight the fires in the Los Angeles area. Currently, reservoirs in the Los Angeles area are mostly full.”

In short, Trump’s stunt was done solely for political purposes so that he could try to score points against Governor Newsom and make demands—backed by Speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA)–concerning how the state checks voter IDs in elections.

As of today, the state has not changed its voting laws or its water policies, but Trump is still threatening to release another 3 billion gallons of water. According to California’s Senator Adam Schiff, it was only thanks to local water managers pleading with the Corps of Engineers as soon as possible that limited the release to 2.2 billion gallons. “I think even the water managers got only a short bit of notice to say, ‘Please don’t. You can’t do that. That’s way too much water,’” Schiff told Newsweek. “And frankly, had they not talked the Army Corps off the ledge, there would’ve been serious flooding. It would have been an even bigger problem.“

Trump never did send federal help while the fires were blazing, although he did order the EPA to send 1,000 staff to help clean up toxic ash in the aftermath. Governor Newsom traveled to Washington, D.C., on February 5, bearing an olive branch. He officially thanked the president for the EPA help in the hopes of getting further aid to the state.

On February 6, Newsom signed an executive order to enact new fire prevention rules, including requiring homeowners to remove flammable plants and materials (except for mature trees) to at least five feet from any structures. Newsweek further reported: “The order also directs CalFire to add 1.4 million acres (nearly 2,200 square miles) to the state’s fire-prone map, bringing more homeowners under these fire mitigation rules. Notably, most neighborhoods that burned in the Eaton Fire were not on the state’s fire-prone map.” It’s important to note that these precautions had already been approved back in 2020 and were supposed to be implemented in 2023, but the state’s Board of Forestry Protection had delayed them. A Washington Free Beacon article opined that the reason for the delay was the tedious environmental review process and red tape.

As of right now, Trump has still not approved federal moneys to help the state with the economic impact, and the president is still threatening to release more water from the north.

Water Sources, Control, and Management

When I first heard about Trump ordering water released from our dams without input or consent from California’s water management authorities, I was outraged. The first thought that sprang to mind was, “We are going to need that water if there’s a drought, and there likely will be soon! Trump is literally going to make California go thirsty.”

The American Revolution started when the Colonists became outraged over taxation from Britain without representation. I feel that taking our resources without our permission—or even asking—is just as bad, if not worse!

One might argue, though, that the Army Corps of Engineers was in charge of the two dams involved, which leads to the question: What water resources do the feds control, and which ones are under California’s management?

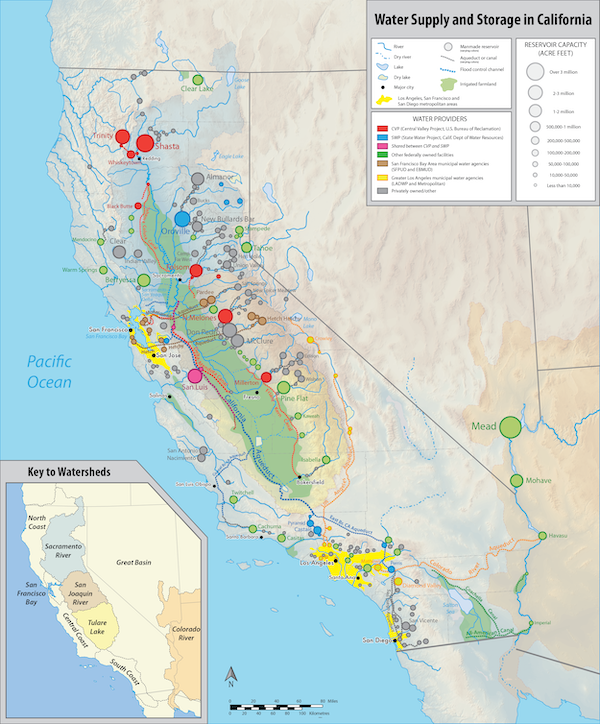

There are over 1,400 dams and 1,300 reservoirs in California. About 75% of our water comes from rain and snow. The bulk of water distribution in California is controlled by three separate projects:

- The Central Valley Project (CVP) was constructed in the 1930s by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which manages it, and moves rainwater and snow melt from Lake Shasta to Bakersfield.

- The Colorado Aqueduct, which was also built in the 1930s and from which California receives a share of the water from the Lower Basin as per the Colorado River Compact. The water that comes to California from the river is managed by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

- The State Water Project (SWP), built in the 1960s and 1970s, is managed by the DWR and supplies 27 million Californians and 750,000 acres of farmland. It includes the Governor Edmund G. Brown California Aqueduct (or, simply, the California Aqueduct), which runs from the Clinton Court Forebay reservoir in Contra Costa County near Stockton, breaks into three branches that lead to Lake Cachuma in Santa Barbara County, Silverwood Lake in San Bernardino County, and Castaic Lake in Los Angeles County.

Although the DWR controls the majority of dams in the state, three federal departments—the U.S. Forest Service, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers—control many important dams, as follows:

- U.S. Forest Service: Fallen Leaf, Hall Mill, Hume Lake

- U.S. Bureau of Reclamation: B.F. Sisk (San Luis), Boca, Bradbury, Casitas, Clear Lake, East Park, Friant, Imperial Diversion, Keswick, Laguna Diversion, Lake Tahoe, Lewiston, Monticello, New Melones, Nimbus, O’Neill, Palo Verde, Parker, Prosser, Shasta, Spring Creek, Stampede, Stony, Trinity, Twitchell, Whiskeytown. (It is important to add here that the Bureau of Reclamation also controls Hoover Dam, which is key in managing the Colorado River.)

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Black Butte, Buchanan, Carbon Canyon, Coyote Valley, Englebright, Farmington, Folsom, Hansen, Hidden, Isabella, Martis Creek, Mojave Forks, New Hogan, North Fork, Pine Flat, Prado, Salinas, San Antonio, Santa Fe, Sepulveda, Seven Oaks, Success, Terminus, Warm Springs, Whittier Narrows

If you think that all of this sounds very complex, you’re right. And we need to do better.

Mistakes of the Past

The history of water use in California is painted with sloppy strokes of waste, mismanagement, and poor planning. Hydraulic mining during the Gold Rush disrupted agriculture with flooding and water poisoned with mercury. Lakes—most notably, Tulare Lake, which was once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi—dried up thanks to farmers’ using the water to irrigate crops indiscriminately. Early settlers in the area, including farmers, ranchers, and speculators, took advantage of the new state’s first-come, first-served policy of giving land claims “senior” status, giving them priority access to water.

The senior status policy favoring old farming families in the state was still in place with the advent of the CVP and SWP, which meant that water distribution policy was unfairly skewed from the beginning. Today, while only 2% of the state’s GDP comes from agriculture, farms and ranches use up 80% of this vital resource.

While agriculture in California will always be important, these dated policies prevent us from moving forward in a digital age challenged by global warming. Dams, reservoirs, and aqueducts alone may prove insufficiently effective in the future. Other policies and planning will be needed to ensure safe and adequate water supplies for all Californians.

The California State Water Resources Control Board

California is still experiencing difficulties with water as a result of policies going back 150 years. There have been longstanding efforts to control and regulate water systems going back to the 1957 California Water Plan that is updated every five years (most recently in 2023). While the plan has no legal authority over water usage, it is used as a resource “by water managers, water districts, cities and counties, and Tribal communities, to inform and guide the use and development of water resources in the state.”

Where the legal authority does lie, however, is with the California State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB), a branch of the California Environmental Protection Agency. Along with nine regional boards under its aegis, the foundation of the SWRCB was established by the Dickey Water Pollution Act of 1949 and solidified under the State Water Rights Board by an Act of 1967.

While the DWR is in charge of reservoirs, dams, and aqueducts, the SWRCB is a higher authority and is in charge of water quality and water rights in the state. It is the SWRCB that authorizes water rights permits to the DWR, as well as all other local authorities, with the exception of pueblo rights and federal reserved rights. This means that it has authority over the myriad of corporations and private entities that control a number of smaller water storage resources across the state.

But the above applies only to surface water sources (lakes, rivers, reservoirs). The SWRCB also has authority over groundwater. In 2014, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) was passed that orders groundwater sustainability agencies to develop sustainability plans for our water.

Mic Drop Time

So here’s the kicker (and thank you for being very patient to read this far).

When Trump ordered the Army Corps of Engineers to release billions of gallons of water from two federally controlled dams, that water—you’ll recall—didn’t happily flow into Los Angeles fire hydrants to put out fires (that, by the way, were already contained by that time).

No.

It went into the GROUND, affecting our groundwater supply without any oversight from the SWRCB, which is in charge of regulating groundwater in accordance with the SGMA.

What the president did was in direct conflict not only with our water needs (especially for farmers in the northern part of the state), but it also wreaked havoc on our efforts to manage groundwater in our own state.

In order for our state to adapt and survive in a future of climate change, it is vital that we have integrated water resource management, including not only quantity but also quality and distribution of all water within the state.

The federal control of water by such agents as the Bureau of Reclamation and the Army Corps of Engineers conflicts with our ability to scientifically and equitably manage California’s fresh water. Therefore, it is time for federal water management to end in this state.

How Do We Do It?

Transfer control of federal property (in this case, dams and reservoirs) to state and local authorities is called a title transfer. In most cases, these title transfers require a bill in the U.S. Congress.

I say “in most cases” because the Bureau of Reclamation has a very limited process for executing title transfers without Congressional approval. So limited, in fact, that it is nearly useless to Californians. If you read the fine print (scroll down to Title VIII), you’ll find that the process excludes the entire Central Valley Water Project (all the big red dots on the map above). And for the title transfers it does allow, it requires “fulfillment of existing water delivery obligations consistent with historical operations and applicable contracts”—so much for Californians deciding what to do with our own water.

Would title transfers mean that the state would have to purchase dams and reservoirs currently under federal control? It shouldn’t, because the cost of the infrastructure has already been paid for by farmers and other water users several times over since it was originally constructed.

Would taking over federal water infrastructure be a major financial burden for California? No. The Bureau of Reclamation’s budget for all of the western U.S. is about 1.6 billion dollars. California’s yearly state budget, by comparison, is about $220 billion; compared to that, the cost of running federal dams is, well, a drop in the bucket. Also, about half of the Bureau’s budget comes from selling water and power, and the other half… appears not to actually be spent; it just ends up sitting in something called the Reclamation Fund. So the real extra cost of taking over federal water infrastructure in California may actually be pretty close to zero.

Legally and democratically, Californians have a mandate to take control of all water resources within our state that supply homes, businesses, farms, and local wildlife with this life-or-death resource.

California politicians rarely talk about ending federal control of water in California, but ordinary Californians are warming to the idea. When the Independent California Institute ran a poll in mid-January, 56% of Californians polled said nearly all federal water infrastructure in California should be transferred to state and local government. And this was two weeks before the Trump administration wasted billions of gallons of our water.

Californians can speed up the process by writing and calling our representatives and senators to pressure Congress to all for title transfers. They could insist, for example, that riders be attached to important bills—such as budget bills—detailing the transfers we require.

If we are to prevent any repeats of the irresponsible waste of our freshwater by the current administration or its successors, in a state where droughts and fires are an increasing concern, then we need tell the feds to take a long walk off a short pier before they drain us dry.