For at least the third time in the last decade, there’s an initiative in circulation that would let Californians start the process of California becoming its own country.

In many ways, California secession is an idea whose time has come. When we polled Californians in January, 61% of them said California would be better off if peacefully became “an independent country with a friendly relationship with the U.S., like Canada.” (Shoot, does the U.S. have a friendly relationship with Canada? It did when I wrote the question!)

Since that poll ran, Donald Trump has been doing pretty much everything in his power—and many things that exceed it—to show Californians that the United States is a cruel, lawless, broken country that only a fool who is dumb as a rock would still want to be part of. Just, so, very bad.

At this point, the #1 barrier to California leaving the U.S. is not legal, political, or economic. It’s in Californians’ own minds. 62% of Californians believe that peaceful, legal secession from the United States is impossible, according to the same poll I just told you about. How can we organize around something we think is impossible?

Hey, 62% of Californians, I’ve got great news! You’re wrong!

Just a normal country!

When it comes to secession, the United States is just a normal country. And in normal countries, secession is legal as long as the national government agrees to it. Which means, if California can get Congress to pass a law creating a process for California to secede, and the President signs it, we can secede, peacefully and legally.

Nevertheless, there’s this persistent, powerful belief that there’s something exceptional about the United States that makes it so, so hard to let a state go. Sure, sure, America is a fully sovereign nation, in control of its own territory and population, but you know, we fought this Civil War, and… the Constitution, we’d probably have to amend it and that’s real difficult, and besides, there’s this court case from the 1860s and our Supreme Court is a big stickler for precedent…

This is nonsense, right? But not just any nonsense; it’s nonsense that’s deeply interwoven into Americans’ sense of identity. It’s nonsense that makes you an important legal expert if you’re willing to repeat it. And it’s not just one nonsense idea, it’s a whole complex of bullshit; if someone calls out one bad argument for why peaceful, negotiated secession is impossible, it’s perfectly socially acceptable to just move onto the next one like nothing ever happened.

In this article, I’m going to call out the five biggest myths around peaceful secession from the United States and knock them down one by one. They are:

- Secession = Civil War

- There’s no precedent in the U.S. for peaceful secession

- The U.S. Constitution has “no mechanism” for a state to secede

- Texas v. White says secession is impossible

- The U.S. can set territories free but not states

But before we do, let’s start out on solid footing: what is secession, and what does it mean under international law?

What is secession?

Well, it’s when part of a country becomes a new country of its own.

Okay, cool. But, what is a country? Duuuuuuuuuude.

Seriously though, there’s a very useful answer to that question. Secession expert Matt Qvortrup, in his handy secession handbook I Want to Break Free, provides three rules about what makes a country a country under international law:

- Is in control of the territory and population

- Is not a puppet state

- Can honor the rights and duties that go with being a state

(By the way, when Qvortrup says “state”, he doesn’t mean a U.S. state; he means a country. That’s how international relations scholars talk.)

“In practice,” he writes, “a state that has a functioning legal system (with courts that can enforce contracts between individuals) is a state.” Which is great, because we already have all that stuff; that’s what the State of California is. So we’re good to go, right?

Not until we clear up a few myths.

Myth #1: Secession = Civil War

With many Americans, if you bring up California becoming its own country, they go straight to talking about the U.S. Civil War. As if there’s no possible way for new countries to be formed other than violence. It’s kind of like, you want to get a new car, but your friend convinces you that the only possible way to get a new car is to steal it, and some guy tried that and got shot by the police, so you shouldn’t get a new car.

Just like there are other ways to get a new car, there are other ways to get a new country. Here are eight well-known countries that were formed through negotiation rather than civil war:

- Hungary separated from the Austrian Empire in 1867.

- Norway seceded from Sweden in 1905 after an independence referendum and negotiations.

- Singapore got kicked out of Malaysia in 1965.

- Canada became fully independent from the United Kingdom in 1982.

- Australia became fully independent from the United Kingdom in 1986, as did New Zealand.

- Czechia and Slovakia were formed out of Czechoslovakia in 1992.

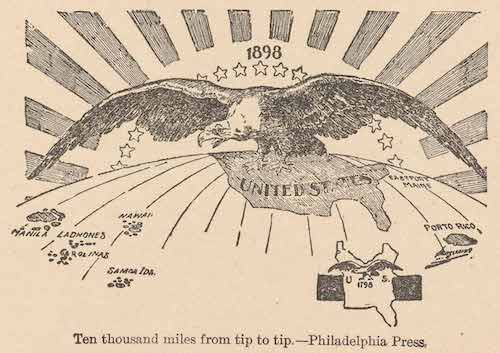

If we’re going to include lesser-known countries, you should know the United States itself let Palau go free in 1982, after it signed a compact of free association. It did the same with the Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia in 1986.

The bottom line is, peaceful, negotiated secession is a real thing with lots of historical precedent, and it’s very, very different from violent, unilateral secession.

Looking at the three rules of countries, it’s pretty easy to see why any country would use violence to stop part of the country from just leaving without permission. That’s a direct threat to rule #1: “control of the territory and population.” If a country doesn’t respond to the threat of unilateral secession, it risks not being a country at all. The United States’ response to the South trying to secede in 1861 was completely predictable and something any country would have done. There’s nothing special about the U.S. in that regard.

In the same vein, international law can’t stop the United States or any other country from deciding to let part of its territory and population go free and become a new country. Being able to make a decision like that is part of what it means to be in control of one’s own territory and population.

If the United States can’t allow part of itself to secede, is it really in control? And if not, is it really a country at all? Duuuuuuuuuude.

Myth #2: There’s no precedent in the U.S. for peaceful secession

You already know this isn’t true because I told you about Palau. But Palau has a population of less than 20,000 people, and its free association status is arguably “independence lite.”

What about a country of more than 115 million people? Say, the Philippines? They were part of the United States from 1898, when Spain ceded it to the U.S., to 1946, when they became an independent country, under a law passed by Congress in 1934.

Yes, an ordinary law, not a constitutional amendment. That law wasn’t caught up in some precedent-shaking legal battle that went all the way to the Supreme Court. The U.S. passed a law outlining a process for the Philippines to become independent, which is exactly the kind of thing a normal country can do. And then, once the Philippines were ready, the President of the U.S. declared them formally independent, and they went their own separate way.

Why did Americans go along with it? Historians today think that a major motivation behind the bill was that, as residents of the U.S. Empire, Filipinos could freely immigrate to the U.S. mainland and (racist) Americans of the time resented that.

Hold up, didn’t the Philippines also fight a war of independence against the U.S.? Well, yes, but that’s not how they became independent. That war formally ended in 1902, and related violence ceased everywhere in the Philippines by 1913. That’s more than 20 years before the independence law was passed! The way the Philippines got independence was by lobbying the U.S. Congress through at least ten independence missions.

Part of why it took so many missions is that the U.S. insisted on the right to have military bases in the Philippines and the Philippine legislature wouldn’t go along with it. Remember how I told you about Palau’s compact of free association with the U.S.? That compact give the U.S. the right to have military operations in those countries and demand land from Palau to operate its military bases. Like I told you, independence lite.

Unlike tiny Palau, the Philippines are one of the world’s 15 largest countries, they’re fully independent, and they got that independence peacefully, through negotiation. So much for “no precedent.”

Still, there are five important differences between the Philippines and California that you should be aware of, helpfully highlighted below in bold:

| Philippines | California |

| About 10% of the U.S. population, at the time it seceded | 11.4% of the U.S. population |

| Independence was requested by the Philippines’ democratically elected government. | 61% of Californians think California would be better off if we peacefully seceded. |

| Declared independence from Spain in 1898 | Declared independence from Mexico in 1836 and again in 1846 |

| At the time, Filipinos were U.S. nationals, not U.S. citizens. | 48% of Republicans think California is “not really American.” |

| Americans didn’t want Filipinos immigrating to the U.S. because they were Asian. | Americans love it when Californians move to their state. |

Myth #3: The U.S. Constitution has “no mechanism” for a state to secede

Prominent legal experts such as Annie Lofthouse of the Walter Clark Legal Group (a personal injury law firm) have pointed out (on TV!) that the U.S. Constitution provides no mechanism for a state to secede.

Technically, that’s true. It’s also completely irrelevant! There’s no specific mechanism in the U.S. constitution for the vast majority of what the federal government does.

For example, the only immigration power the Constitution explicitly grants to congress is “To establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization.” And yet, somehow, Congress manages to pass legally binding immigration laws, providing for border controls, deportations, H-1B visas, and so on. How?

Congress’ own website readily admits that “while Congress’s power over immigration is well established, defining its constitutional underpinnings is more difficult” (sounds a lot like “no mechanism” to me). Then it goes on to say:

Since the late nineteenth century, the Supreme Court has described the power as flowing from the Constitution’s establishment of a federal government. The United States government possesses all the powers incident to a sovereign, including unqualified authority over the Nation’s borders and the ability to determine whether foreign nationals may come within its territory.

What would give Congress the ability to pass a law to let a state go? The exact same thing: “unqualified authority over the Nation’s borders.” We’re pretty much back to the three rules of countries under international law. “Powers incident to a sovereign” sounds a lot like “in control of the territory and the population” and “can honor the rights and duties that go with being a state.”

Why put a personal injury lawyer on TV to gaslight Californians about the legality of negotiated secession? Well, that’s pretty normal for countries too. As Qvortrup writes, “The governments of most countries don’t like to be dismembered. So, they will resist and say that the independence is illegal.”

Telling Americans that the Constitution does not allow secession in any form is a patriotic exercise, just as much as pledging allegiance to the flag or singing “America the Beautiful.” Suuuuure, the U.S. is one nation, under God, indivisible. In the same way that its gleaming alabaster cities are undimmed by human tears.

What do actual legal experts say about the constitutionality of secession? In his latest book, No Democracy Lasts Forever, Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law, writes simply “we may want to believe that secession is unconstitutional, but nothing in the Constitution or its history supports that conclusion.”

Next time someone tells you there’s “no mechanism” in the U.S. Constitution for a state to secede, politely ask them to point out for you the specific article, section, and clause of the Constitution that gives ICE the ability to deport people. No worries, friend, take all the time you need!

Myth #4: Texas v. White says secession is impossible

Another favorite of “legal experts” is the 1869 U.S. Supreme Court case, Texas v. White. As Annie Lofthouse tells us, “states cannot secede unless through revolution or with the consent of all other states.” Though… she also calls it “White v. Texas.” Maybe it’s worth taking a look of our own?

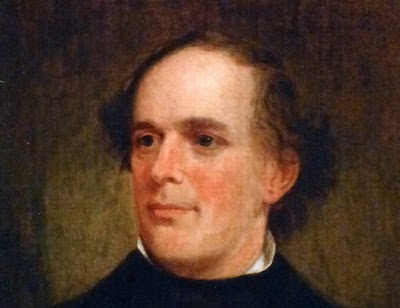

On its face, Texas v. White is about something really, really boring: the State of Texas sold 163 U.S. government bonds in its possession to raise money to a brokerage, co-owned by one George W. White and his partner, John Chiles. (Yawn.)

Here’s the part that makes it interesting: Texas used the money from that sale to finance civil war against the United States. In 1869, four years after the Civil War ended, the State of Texas sued to get its bonds back, claiming the sale of the bonds was illegal and thus, invalid.

In its decision, the U.S. Supreme Court began their argument by saying that states could not unilaterally secede from the United States:

It is needless to discuss, at length, the question whether the right of a State to withdraw from the Union for any cause, regarded by herself as sufficient, is consistent with the Constitution of the United States.

Which, good, that’s normal for countries. Glad we cleared that up!

From there, things kind of went off the rails. According to the Court, legally speaking:

- The U.S. Constitution didn’t replace the Articles of Confederation, it just made them “more perfect”

- Texas never actually left the United States

- During the Civil War, Texas’ was taken over by an “insurgent government” who took illegal actions on behalf of a “hostile confederacy” (which, presumably, was never actually a country)

- The bonds were never legally sold to White and Chiles in the first place. They stole them, basically? Anyway, they had to give them back.

Parts of the decision get crazy flowery, like this gem:

The act which consummated her admission into the Union was something more than a compact; it was the incorporation of a new member into the political body. And it was final.

First of all, ew. Second, why bother with all that legal fiction (erotic and otherwise)? Who cared if post-Civil War Texas got their stupid bonds back anyway?

Well, people who wanted Reconstruction to end and the U.S. to just go back to its pre-war normal, that’s who. If, legally, the Confederacy really had seceded, then the confederate states were legally just conquered provinces, and their residents were conquered peoples, for the United States government to do with as it wished. The point of Texas v. White was to close off that line of reasoning and put things back the way they were before the Civil War, so that (white) people could go back to business as usual.

So maybe it’s not such a surprise the decision in Texas v. White flatly contradicts the plain language of the U.S. Constitution: it says the Constitution “looks to an indestructible Union composed of indestructible States.” But states aren’t indestructible! As anyone who’s read Article IV, Section 3 can tell you, the actual U.S. Constitution lays out the necessary preconditions for a new state to be “formed by the Junction of two or more States,” extinguishing the states’ existence.

The judges who wrote the decision must have known that too, but they made stuff up to get the outcome they needed. Think of it as the Bush v. Gore of its generation.

Imagine, now, that Congress passes a law allowing California to secede from the U.S., and that law comes before the U.S. Supreme Court. If, hypothetically speaking, the Court makes its rulings with respect for long-established precedent, would Texas v. White matter?

Nope! Not everything in Supreme Court decisions actually becomes precedent—only the parts that were necessary to resolve the case. Everything else is dicta—literally, “something said in passing.” Texas v. White was, fundamentally, a case about whether the U.S. could allow unilateral secession. Anything the decision from that case says about negotiated, mutually-agreed upon secession is dicta, including that part that Annie Lofthouse quoted.

Misquoted, really. Here’s what it says, in full: “The union between Texas and the other States was as complete, as perpetual, and as indissoluble as the union between the original States. There was no place for reconsideration, or revocation, except through revolution, or through consent of the States.”

People who support California independence sometimes fixate on “through consent of the States.” As if Texas v. White created some magical process we could use to negotiate secession, if only we knew what it was! Does “consent of the states” mean a majority of U.S. Senators (who represent states)? A majority of state legislatures? Three-fourths of the state legislatures, passing a Constitutional amendment? All of the states, for some reason that only Annie Lofthouse knows? Aaaaaa, what does it mean?

Relax. It doesn’t mean anything. It’s dicta. Just, some stuff the Court said in passing.

So what should our hypothetical precedent-following present-day U.S. Supreme Court do with our hypothetical California secession law? Where should they look for precedent?

Here’s the fun thing about all the legal fiction in Texas v. White: If, somehow, the case still stands as legal precedent today, then technically, Texas and other confederate states never seceded—they just got taken over by a “confederacy” of insurgents. Meaning that the only precedent for secession in the United States is the peaceful, negotiated kind: the Philippines, Palau, Cuba, and so on. That’s the precedent that matters.

Myth #5: The U.S. can set territories free but not states

Americans take it for granted that if Puerto Ricans ever vote for independence, the United States could let them become their own country, just like they have with other former U.S. territories. In fact, some people speculate that the Trump administration is intentionally trying to push Puerto Rico out. To save money, or something?

If Puerto Rico can leave, why not California? What’s the difference?

Remember, when we’re talking about negotiated secession, what we’re really talking about is the United States giving up control of part of its territory in an orderly fashion. It doesn’t matter to the rest of the world that California is a U.S. state and Puerto Rico is a mere U.S. territory, any more than it matters to us which Russian federal subjects are Krais and which ones are Oblasts. As far as international law goes, California and Puerto Rico are both just land the U.S. has sovereignty over.

But maybe once land becomes part of a U.S. state, it becomes part of the U.S. forever? Like, *cough*, another member entering the political body? In perpetual union?

I can tell you that’s definitely not true. The United States gave a big chunk of Maine to the British in 1842 under the Webster-Ashburton treaty. Today, what used to be part of Maine is now part of Canada. (Is that why Trump wants to make Canada the 51st state? To avenge Maine?)

But wait, if the U.S. can give up part of a state, what’s stopping it from giving up an entire state?

Article V of the Constitution says, “no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate.” Which pretty strongly implies that Congress can’t unilaterally kick California or any other state out of the U.S., because then we’d lose our two Senate seats! And that would be so… unequal! (Puerto Rico, being a territory, has no such guarantee.)

But if California consented to be removed from the United States, I don’t see any constitutional principles that would stop Congress and the President from making that happen.

Honestly, the only constitution that matters here is California’s. We’d definitely have to fix that section that says we’re “an inseparable part of the United States of America.” But changing California’s own constitution is so easy, we do it every other year. The Philippines changed their constitution in anticipation of independence, and we can too!

And look, even if you believe Texas v. White’s nonsense and assume that states are “indestructible,” there’s still a way to make a new country where California is now, without the State of California technically ever leaving the United States. It’s just stupid complicated.

Please, can we not? California deserves the same consideration as the Philippines: an ordinary law, laying out an orderly process of secession.

Sure, aggrieved U.S. citizens living in California might challenge that law, arguing that they’re being deprived of their right to live in the United States. But how, exactly, would California secession impair their rights? The U.S. couldn’t revoke their U.S. citizenship except for a very specific list of reasons. They’d have basically the same set of rights under California’s constitution as under the United States’—in some ways, better versions of those rights. And if they wanted to live in the United States, they’d be free, as U.S. citizens, to move there.

Knowing the current, non-hypothetical U.S. Supreme Court, they’d probably reject that case for lack of standing, avoiding the issue entirely.

But they’ll never agree to it!

Okay, fine, you might say, I get it, all California secession needs from the U.S. is an ordinary law passed by Congress. But they’ll never pass a law like that, so it doesn’t matter.

And now we’ve left the realm of verifiable facts and moved into speculation about what’s politically possible. Mythbusting, complete!

Maybe no matter how hard California lobbies for independence, no U.S. President will ever negotiate with us, and no U.S. Congress will ever grant California permission to leave. Honestly, I’m a native born California who’s followed American politics for my entire adult life, and the more I learn about it, the less I understand. You tell me!

Here are three things I can offer:

First, would it be stupid of the United States to give up California? Well yeah, we’re pretty great! But as far as stupid goes, would letting California secede rank be anywhere near as stupid as mass firings of federal employees, or sparking a global trade war for no discernable reason? Because these things are actually happening right now. How about invading Iraq in 2003? Where does that fall on the stupid scale? Just because it’s stupid doesn’t mean the United States won’t do it.

Second, I’ve heard from many, many people that the United States wouldn’t let us go because other states are dependent on California’s federal tax dollars to stay afloat. But that’s simply not true. When (mostly red) states get more federal spending than they pay in federal taxes, that money comes almost entirely from federal borrowing, not California and other “donor states”.

But, doesn’t the United States’ ability to borrow money depend in part on being able to collect taxes from Californians? Yes. And that sounds like the kind of thing a very smart person might worry about.

Third, I apologize if I gave the impression that secession would be a simple matter of California voters passing a ballot measure, and Congress and the President kind of shrugging and saying sure, whatever, we never really liked you anyway.

Of course that wouldn’t happen. It would probably take every bit of leverage California had to bring the federal government to the negotiating table at all, much less to get a fair deal.

But California has that leverage. We elect about an eighth of the U.S. House of Representatives, and Congress already can barely find the votes to pass the budget, raise the debt ceiling, and deal with other must-pass legislation. And we know Californians are willing to play hardball because we polled them: in January, 63% of Californians said we’re “justified in using hardball tactics in the House to gain greater autonomy for California.”

What would that look like? Congress tries to pass a budget. Californians say, you want to pass a budget? We want independence. The federal government shuts down. You want the government to reopen? We want independence. The debt ceiling is about to be hit. You want to protect the full faith and credit of the United States? We want independence.

Now imagine it’s not just California, but other states who also think they could do better on their own, too. Does it still sound like the U.S. would never negotiate secession?

What do you want to do?

That’s why for me, the big question isn’t “could California secede?” It’s “what do Californians want to do?”

California independence is a nation-state of mind. If Californians put our minds to it, there’s nothing we can’t achieve.

Want to find out what other Californians want to do about secession? Donate to our next poll.

And if you think there’s any chance you’d enjoy looking at a bunch of graphs with me as much as you just enjoyed learning about international law and a Supreme Court case from the 1860s, definitely check out What it Means to be a Donor State.