How the U.S. could set a state free, without a constitutional amendment

Could the United States let a state become an independent country, if the political will existed to do so? Or would such an effort founder on the United States’ extremely high bar for amending its constitution?

In this article, I’m going to demonstrate that although the United States does not include a direct process for granting independence to a state, it has enough other powers that it can effectively do so anyway.

To be clear, I’m not arguing for a new interpretation of the U.S. Constitution here (e.g. arguing that the process for admitting states ought to be reversible because of symmetry or something).

What I’m saying is, if you use nothing but powers that we all agree that the federal and state governments have, under the U.S. Constitution as we currently understand it, you can create a process where you start with a state… and end up with a country.

Let’s see what this country can do!

Okay, for starters, let’s take a look at Article IV, Section 3, Clause 1 of the United States Constitution, which explains how new states may be admitted to the union. Maybe we missed something? Here’s what it says:

New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new States shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.

Nope, not much help. States can be admitted to the union, and split up or combined with other states, but it doesn’t say anything about how to get out again.

Well, what else do we know about the United States?

(i) States can cede territory to the federal government

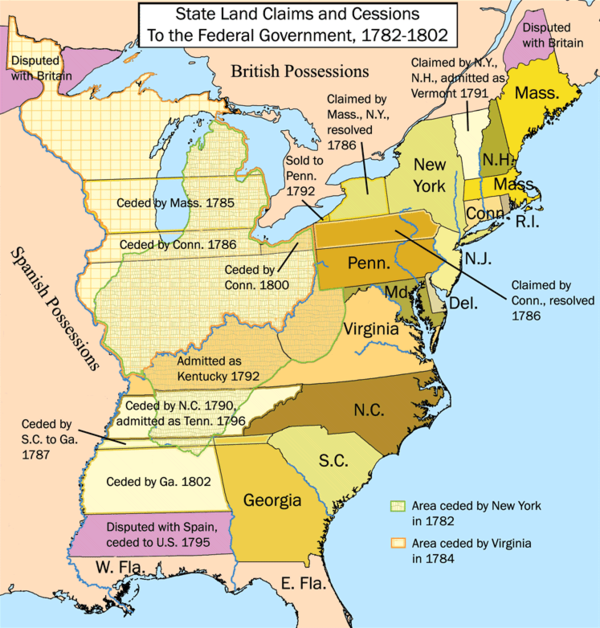

We know this because a whole bunch of states did it soon after this country was founded.

The current constitution didn’t take effect until June 21, 1788 (before that we were on the Articles of Confederation, ewww), so cessions before that date don’t tell you much. But both Georgia and North Carolina ceded nearly half their territory to the federal government while we were operating on the current U.S. Constitution.

(ii) States can grant publicly owned property to the federal government

Buildings, real estate, cars, money… I think this is uncontroversial enough to require little further explanation.

It would be very helpful for the plans below (but not vital to the point of this article) to be absolutely confident that states can transfer contracts to the federal government as well. For this, I’m just going to point out that contract law is determined by states.

(iii) The federal government can grant independence to territories

This should be unsurprising because Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution says the federal government can do pretty much whatever it wants with territory it controls, through ordinary acts of Congress:

The Congress shall have power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed as to Prejudice any Claims of the United States, or of any particular State.

What about precedent? Former territories granted independence by the U.S. include:

- Cuba (1902)

- The Philippines (1946)

- Palau (1994)

In some cases, these countries gained independence through a treaty (which requires the consent of the U.S. President and 2/3 of the U.S. Senate), whereas in others, it was done by an ordinary act of congress (president + majority of both houses of Congress). Cuba gained independence (from the point of view of the U.S. legal system) through an amendment to a U.S. army appropriations bill.

Also, note that although Cuba and the Philippines fought a war for independence from the U.S., Palau became independent peacefully.

Great! With these three powers, we’re all ready for our first example.

Because this is a site about Californian independence, I’m going to use California for my examples, but in principle, this should work with any state (Free Delaware!), or even a group of states.

Plan A: Ja ne*, Jefferson!

(* Japanese for “see ya”)

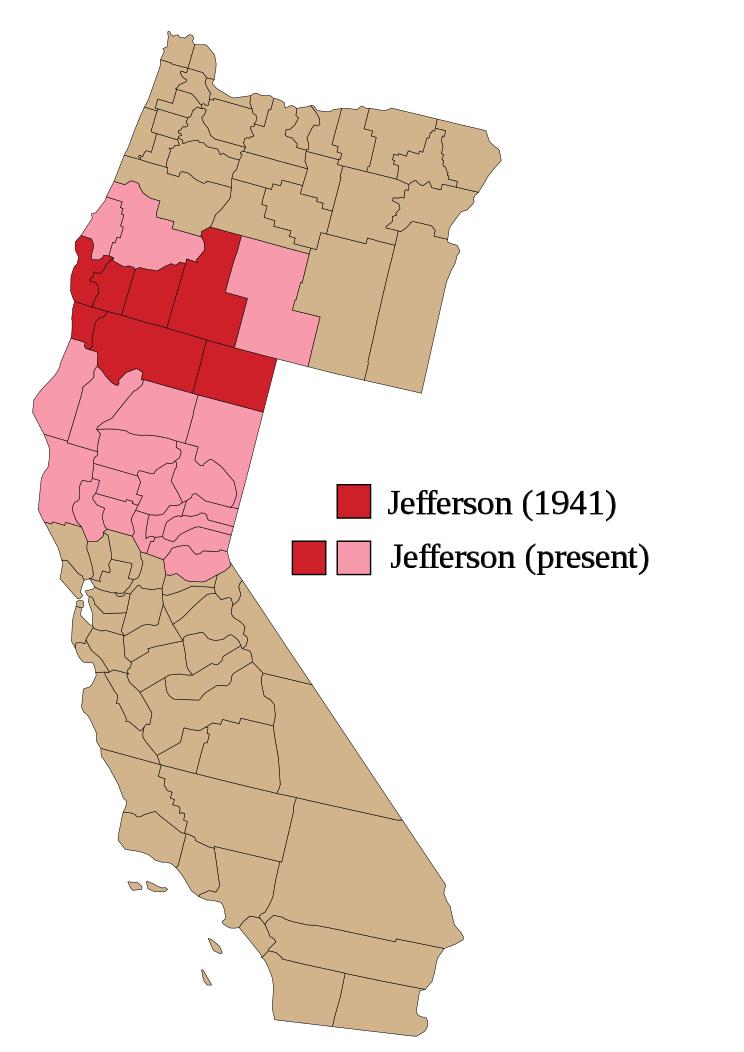

California has its own internal secessionist movement: since 1941, at least some of the residents of the far northern part of the state have wanted to break off and form a new state called Jefferson.

Great idea! We can use that!

Being a proposed state, Jefferson has no fixed boundary, consisting of anywhere between three and 21 California counties (plus some counties in Oregon, but let’s not get into that).

This is my article and I’d like to see the Central Valley kept intact (for its mountainous defensible borders? Nah, way more important that that: the California State Water Project). So for this example, I’m going to define Jefferson as just the original three counties shown in red at the north end of the state.

How does granting Jefferson it’s long-yearned-for statehood help California become an independent country? Basically, you turn everything south of Jefferson into a territory, and then the U.S. grants that territory independence.

Here’s how it would work, step by step:

Step 1: California cedes all territory south of Jefferson to the federal government

California can do this because (i) states can cede territory to the federal government.

Step 2: California transfers all public property within this territory to the federal government, plus the bulk of the state treasury and other state-owned investments.

Because (ii) states can grant publicly owned property to the federal government.

Under the California Constitution as it currently stands, the state government probably couldn’t transfer city-owned property. Not an issue; we’re assuming that the California Constitution (which is relatively easy to amend) is already all set up for independence and has taken things like this into account.

Step 3: The federal government uses the ceded territory to form the Territory of California

As far as U.S. law goes, you might want to think about whether U.S. territorial waters needed to be attached to the Territory of California as well. Since we’re talking about forming a new country here, it’s probably mostly a moot point; the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea standardizes countries’ territorial waters, exclusive economic zone, etc.

You would want some clarity about exactly how the new California/Jefferson border extends 200 miles out to sea, to prevent future conflicts.

Step 4: The federal government grants the state-owned property from Step 2 to the Territory of California

Steps 3 and 4 are just the federal government shuffling its own stuff around.

It would make a lot of sense for the federal government to grant federally owned lands and other property to the Territory as well; not much point owning and attempting to manage a forest in a foreign country. The United States and California would have to work out the details; in any case, the big-ticket item in negotiations would be not federal property, but the national debt.

5. The United States government grants independence to the Territory of California, with a constitution identical to the current California Constitution, by an act of Congress

Which it can do because of (iii). Voilà! Independent country.

And congratulations, Jeffersonians, you are now the proud owners of the State of California and can rename it or amend its constitution as you see fit.

The magic of interlocking legislation

Okay, so, technically, I’ve proved my point. So what? How could California trust the U.S. to follow through? What if it gets stuck as a territory?

Not to worry. This could be made to work in practice through interlocking legislation.

Basically, California’s constitution is revised to say that the state will do steps 1 and 2 just as soon as Congress passes legislation saying that it will do steps 3–5. The actual text of such federal legislation could be worked out in advance through negotiations between California and the United States (which would be absolutely necessary for anything like this to happen) and even spelled out explicitly into the California Constitution (“at such time as the United States government passes legislation with the following text the State of California cedes…”).

In other words, yes, this is a real thing that could actually happen. It’s not as clean as Congress simply granting independence by majority vote, but it doesn’t require any more elected officials’ votes, just more lawyers.

A question of political will

Now, that doesn’t mean this will happen anytime soon. You’d still need:

- Broad political consensus within California

Basically enough to revise the state constitution, which would take 2/3 of both the state Assembly and Senate, and a majority of voters.

Legislators bend to the will of the voters (especially if they they’re considering later running for office in a new country whose existence they opposed), but still, the will of the voters isn’t there yet. Currently, when polled, only about 23% of Californians answer Yes to the question “Would you support? Or would you oppose? … the idea of California seceding from the United States?” (Peacefully through negotiation, I hope!)

It’s worth noting that 20% of the respondents to the survey question replied “Not Sure,” and I’d like to commend these folks on their honesty. Realistically, probably less than 1% of Californians have given this question any serious thought. Why bother, if it’s impossible without amending the U.S. Constitution?

Also, arguably, this poll is probably just picking up the baseline of about a quarter of Americans in any state who say their state should secede. (Free Wyoming!)

Anyhow, say, hypothetically, that Californians eventually do think independence through and a majority decide it’s a basically solid idea. Then you need:

2. An agreement in principle between the United States and California

At the very least, you’d need a U.S. president who’s willing to negotiate. And then, say, that president and California’s governor (plus, probably, a handful of other elected officials) would have to hash out the details of things like military bases and water from the Colorado River.

America, let’s make a deal!

Finally, you’d need:

3. Weak political consensus in the United States

This is the point where the plan above (and the others, below) matter. You’d have to get a majority of votes in the House of Representatives (pretty doable, since an eighth of those seats are California’s) and the Senate (where California only controls one-fiftieth of the seats, so better start convincing people).

What you wouldn’t need is any support whatsoever from the legislatures of other states, as you would for a constitutional amendment. New Hampshire, should you object to this plan, please do be so kind as to bring it up with your U.S. Senators.

In fact, you wouldn’t necessarily need majority support of the American public (which, again, is one-eighth Californian), since it’s not going to be put to a national vote.

Plan B: The Whole Banana

What if Jeffersonians didn’t want to be left behind? Maybe because the idea of splitting from California appears to have less than majority support when put before actual voters, or maybe because Jeffersonians decide they’d rather take their chances with one distant government that mostly ignores them instead of two.

Could California just give the federal government all the territory (step 1, above) and all the public property (step 2), effectively extinguishing its existence and/or reverting itself to territory status?

You’re welcome to try arguing this in court, but I don’t think this is something that can definitely happen under the U.S. Constitution as we currently understand it. So it’s not going to happen in this article.

What if rather than leaving three counties behind, we just left a tiny bit of land, with no other public property?

Legally, this would be equivalent to Plan A, above.

The problem is, that tiny piece of land would still technically the be the State of California, granting whoever camps out on it the right to elect two U.S. senators, etc. While this sounds like a lovely way for California to troll the United States, I don’t think this is something that would be agreed to in negotiations.

The solution is something we’ve already seen, above:

(iv) States can be joined with other states

To my knowledge, this hasn’t ever been done, but it’s right there in the plain language of Article IV, Section 3, Clause 1:

New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new States shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.

So as long as we can get one other state to agree to absorb the tiny bit of California we leave behind, we’re golden. The simplest thing to do would be to leave behind state-owned land on the border into a neighboring state. For example the California side of these islands in the Picacho State Recreation Area.

Behold, the Great State of California! (In the middle there, to the left of the dotted line. See, it has the word “California” written right on it.)

Really, though it could be any bit of California’s land, joined to any state. States don’t have to be even remotely contiguous: Maine was part of Massachusetts until 1820. And if that state didn’t want California’s stinkin’, free-thinkin’ territory, they could always (i) cede it back to the federal government.

Here’s what the revised plan for independence looks like, step by step

Step 1: The California and Arizona legislatures vote to join the states, under Arizona’s constitution, if California’s territory ever becomes smaller than one square mile.

Step 2: California cedes all territory, other than California’s half of the two islands on the map above (and some water around them) to the federal government.

Step 3: California cedes all public property (other than the state-owned land on the islands) to the federal government.

Maybe leave something behind for Arizona as a thank you gift, perhaps some state bonds or a nice portrait of Governor Ronald Reagan.

Steps 4–6: Same as steps 3–5 above

Create the Territory of California, give it its stuff back, grant the Territory independence. No biggie.

Step 7: Congress votes to allow the State of Arizona and the remnant “State of California” to merge

As in Plan A, this could all be accomplished with interlocking legislation. Because of the language of the U.S. Constitution, the California legislature would have to vote explicitly in Step 1 (it can’t happen automatically in California’s Constitution), but that doesn’t have any effect unless the rest of the plan goes through.

A possible stumbling block

Are you familiar with the Insular Cases? I mean, who doesn’t spend their spare time brushing up on U.S. Constitutional law just for fun, so probably, right? But just as a refresher:

The Insular Cases established the idea that there are two different kinds of U.S. territories. There are incorporated territories, which are (with one exception), the states and Washington D.C., where the U.S. Constitution is the law of the land.

And then there are unincorporated territories, including Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa and the like, which are, technically, just stuff that the U.S. government controls. People born in Puerto Rico gain U.S. citizenship by birth just like people born in the states, but it’s because Congress passed a law saying so, not because of the Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment. American Samoa has a different arrangement, for example.

So far, every time the U.S. has (iii) granted independence to a territory, it’s been an unincorporated territory.

I’m not sure this matters. The language of Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2 is pretty darn broad.

Also, Palmyra Atoll is an incorporated territory (it’s a leftover bit of the Territory of Hawaii that never made it into the state). If the Nature Conservancy volunteers and government scientists who camp out there found a way to make the island habitable and wanted to become an independent country, I don’t think anyone would be writing in solemn tones about how we are one nation, indivisible, and that that could never happen anyhow without a constitutional amendment.

Still, this isn’t an article about how we ought to interpret the Constitution. Let’s suppose courts rule that power (iii) can’t be used to grant independence to former state territory. Are we stuck?

Ha. Of course not.

Getting unstuck

Something else we know about the United States is:

(v) the United States has broad discretion to recognize foreign governments

This stems from Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution:

[The President] shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur…

It doesn’t matter for the purposes of this article (we’re going to need that treaty power), but in some cases, the President can recognize another government (exchanging ambassadors, etc.) without even first getting the consent of the Senate.

(vi) the United States can cede land to foreign governments

This is done by treaty (president + 2/3 of the Senate). This didn’t happen very often (the U.S. won a lot of wars), but it definitely happened. For example, the United States ceded the portion of the Louisiana Territory north of the 49th parallel to Britain under the Treaty of 1818.

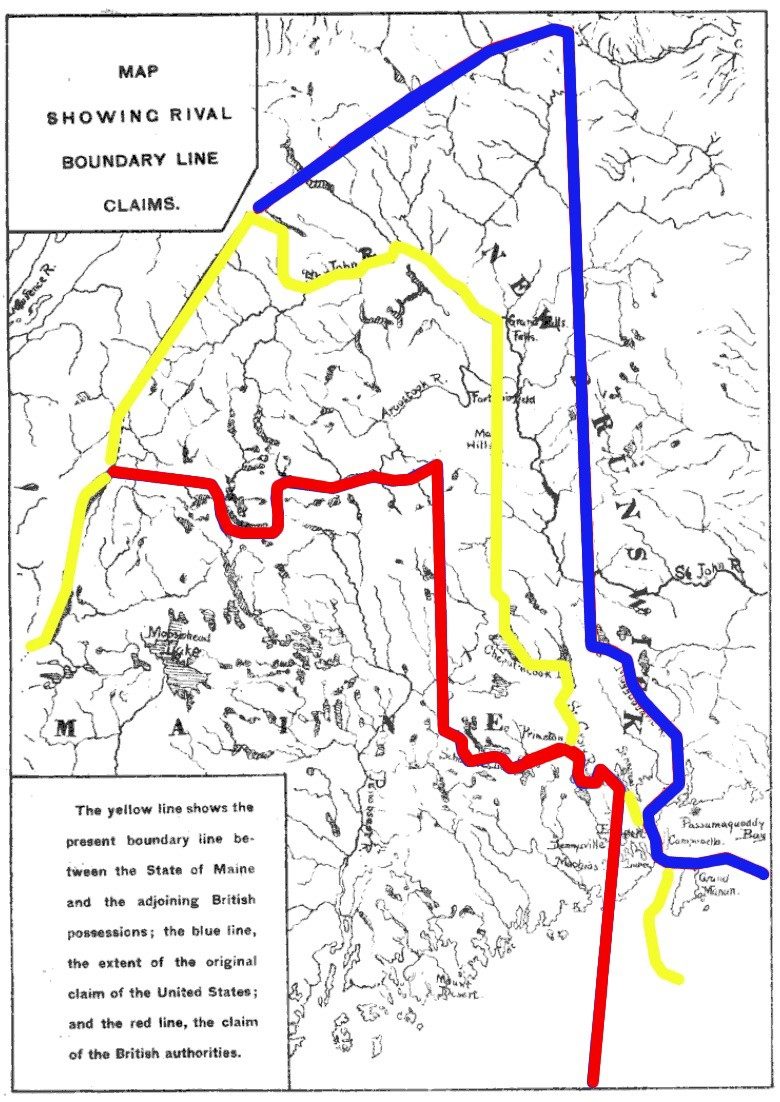

Well, sure, but what about territory that used to be part of a state? Check out the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842, which ceded land belonging to Maine to the British North American Colonies (basically, Canada). Everything below between the yellow and blue line was once (so Maine claimed) rightfully Maine’s:

(vii) the federal government can grant property it owns to foreign governments

Because, treaties. I don’t think this is controversial.

That’s all we need; we’re back in business.

Plan C: The Republic of California in Exile

For this plan, the United States needs to invent a foreign government of the Republic of California in Exile, which, of course, just happens to operate under a constitution identical to California’s, or would, if it only had its country back. Perhaps the U.S. could grant it an embassy in Redding, CA.

This sounds totally silly, and it is, but it’s also totally legal, because of (v) the United States’ broad power to recognize foreign governments.

You’ve probably guessed what happens next. Rather than granting California’s territory and stuff to the Territory of California, which is then set free, we grant it (by treaty) to the Republic of California in Exile, which is (by treaty) already recognized by the United States as an independent country. Here’s what it looks like, step by step.

Steps 1–3: Same as above

California gives everything except a tiny piece of land to the federal government, and prepares to be joined in eternal union with Arizona.

Step 4: The federal government formally recognizes the State of California in Exile as an independent foreign nation

Step 5: The federal government cedes California’s territory to the Republic of California in Exile

Which it can do because of (vi), ceding land to foreign governments.

Step 6: The federal government cedes California’s public property to the Republic of California (now no longer in Exile)

Which it can do because of (vii), granting property to foreign governments.

And we’re done; California doesn’t need to be granted independence at this point because was already recognized as independent in Step 4.

Oh wait, right, joining the leftover bit of the State of California to Arizona. Almost forgot!

Step 7: Same as above

Unlike plans A and B, this relies on treaty power (president + 2/3 of senate) rather than acts of Congress (president + majority of each house of Congress). This changes the political calculus a bit, but it’s way, way easier than amending the U.S. Constitution. And it still works as interlocking legislation; steps 4–6 could all be part of the same treaty.

Okay, what if courts rule this is way too cute, and can’t happen? We’ve got one more ace in the hole.

Plan D: Two for the price of one

Something I glossed over in the examples above is that Indian tribes are sovereign nations. Indian reservations (which not all tribes have) are land held in trust for tribes by the U.S. government.

Something to think about in any independence scenario is that the status of Indian nations isn’t going to change without their consent. An Indian reservation in an independent California would still technically be U.S. land (held in trust for the tribe) until three-way negotiations between the United States, California, and the tribe on that reservation conclude otherwise.

This doesn’t seem like a sticking point that would sink U.S.-California independence negotiations, but it does present an opportunity. Namely:

(viii) the United States can grant independence to an Indian nation by treaty

I unfortunately don’t have precedent for this, but c’mon, the argument against this is pretty darn thin. The United States has fought wars and signed treaties with Indian nations. They existed before the U.S., and never, ever signed up for being part of a perpetual union of states.

So then, rather than granting California’s territory and stuff to a made-up nation, we grant it to a real one, which then sets California free.

I think it’d be disrespectful to single out a random Indian nation for this example, but I just want to point out that there are more than 100 federally recognized tribes in California (and there’s nothing that, in theory, rules out a tribe located in another state).

Here’s what it looks like, step by step:

Steps 1–3: Same as above

Step 4: The United States grants independence to Unnamed Indian Nation

By treaty (viii). Once this happens, Unnamed Indian Nation is an independent country; if it wants to have 39 million Californians as (extremely temporary) members, U.S. law regarding Indian affairs no longer applies.

Step 5: The federal government cedes California’s territory to Unnamed Indian Nation

Which it can do because of (vi).

Step 6: The federal government cedes California’s public property to Unnamed Indian Nation

Which it can do because of (vii).

Step 7: Same as above

California and Arizona, solemnly joined in eternal union.

Step 8: Unnamed Indian Nation keeps some land and property for itself and grants the rest back to the newly independent Republic of California

Lots of state or federal land around to make Unnamed Indian Nation big enough to be a viable country.

And we’re done, now with not one great new country, but two! Hopefully California and Unnamed Indian Nation will sit next to each other in the United Nations.

It would be a lot more complicated, but I’m pretty sure you could still pull this off through interlocking legislation as well. Convoluted as this scheme is, it would still work in practice.

Probably not justiceable?

A couple times above, I’ve said “if the courts decided…”. Pragmatically, this might never be an issue, because by the time the courts issued a ruling, California would already be an independent country.

I don’t mean to play coy about the Constitution; like I said, though the combination of steps in the plans above are novel, I believe the powers of the U.S. government they invoke are fairly uncontroversial.

What I mean is this: imagine a scenario where a U.S. president opens negotiations on independence with California in good faith, California prepares its constitution, and Congress passes the requisite interlocking legislation to set California free, also believing in good faith that what they’re doing is constitutional.

Then imagine sometime later, some people in the United States allege that the process for granting California independence was not, in fact, allowed under the Constitution, that they’d been harmed by this, and that they want their day in court.

At this point, whatever U.S. courts ruled, it couldn’t possibly affect California’s status as an independent country. Even the U.S. Supreme Court wouldn’t be the right venue; you’d want to take it up with the International Court of Justice, or the United Nations.

Conclusion

The U.S. was founded as an expansionist project based on the idea of a perpetual union of states, and the U.S. Constitution’s lack of an explicit process for granting independence to a state reflects this.

However, whatever the intent, the United States Constitution is not airtight. It grants the United States government ample discretion over territory and property, and broad treaty powers. The United States established early on that territory belonging to a state can be later given up, and the the United States’ forays into colonialism created clear precedent that territory once annexed could be later granted independence.

In short, the United States Constitution contains not an implied power to grant independence to states (i.e. arising as the result of legal interpretation) but an effective one to achieve the outcome of granting a state independence, without ever doing so directly.

Granting California or any other state(s) independence might be a good idea or a bad one, depending on the particulars. What it is not is a fanciful idea, to be waved away because of the near-impossibility of amending the U.S. Constitution.

This is a real thing we could actually do. The question is whether we want to.

This article originally appeared in California Rising.