This article outlines a simple way that any U.S. state can:

- control the total amount of taxes (state and federal) that state residents and businesses pay

- stabilize the total level of government spending (state and federal) in a state

- recapture federal tax expenditures for the state’s own purposes

This plan requires not some complex constitutional shenanigans, but simply:

- changes to the state tax code

- basic arithmetic

Since this is a blog about California, I’m going to explain how this would work here, but really, any state could pull this off. The states particularly well suited to this plan are the ones with the highest state income taxes already: after California, these are Oregon, Minnesota, Iowa, New Jersey, Vermont, New York, Hawaii, and Wisconsin.

Background

Following the November 2016 election, it seems very likely that the federal government will soon do the following two things:

- cut taxes for high-income earners

- cut funding for Medicaid

Medicaid is a state-administered federal program (in California we call it Medi-Cal), so fixing this is almost entirely a matter of funding. A straightforward solution for California (and other states that believe families and low-income individuals should have access to health care) would be:

- raise taxes on high-income earners

- use that money to fund Medicaid in the state

In fact, this solution would apply to most of what the federal government does in California, or any other state. Check out Ezra Klein’s article The U.S. Government: An insurance conglomerate protected by a large, standing army, where he makes that point that:

- other than the military, the primary activity of the federal government is cutting checks

- changes in spending almost entirely affect health care and other social services

Great! So now that we’ve solved Medicaid/Medi-Cal funding, all we have to do in California is apply the exact same solution to:

- TANF (“welfare”), administered by California as CalWORKS

- SNAP (“food stamps”), administered by California as CalFresh

- SCHIP (children’s health care), administered by California as Healthy Families

- health insurance subsidies for the ACA (“Obamacare”), administered by California as Covered California

- federal funding for the Central Valley Project

- any of the various federal grants that go to California for transportation, renewable energy, education, water, the environment, or basic research

Ugh. This is starting to get complicated. Can’t we… automate this somehow?

At least as far as revenue goes, yes, yes we can. Here’s how it would work.

The awesome power of… subtraction?

Currently, California’s Revenue and Taxation Code defines the amount of income tax residents pay in addition to federal income tax. The state takes its cut, and so does the federal government, with no coordination between them on tax rates. They can both cut or both raise your taxes in the same year.

Instead, I’m proposing that the California tax code determine the totalamount of state and federal income taxes that residents and in-state businesses pay.

How can a state do that, without the consent of the federal government?

Through the awesome power of subtraction.

In essence, the California would determine its own tax rates and tax code, and make federal income taxes fully creditable against state income taxes.

What this would look like to taxpayers is you’d now fill out your state tax return to calculate your combined state and federal tax, subtract the amount you owed in federal income taxes, and that’s how much you’d send to the state.

A deal the feds will never offer

This would mean two very good things for California taxpayers:

Federal tax rates no longer matter

Congress: raise our taxes, cut our taxes, don’t care, don’t care, don’t care; what Californians pay under this system is the same.

In fact, if you think about it, this means the federal tax code would no longer matter to taxpayers, except insofar as the state tax code referenced it. (More about that later.)

Californians could set their own tax rates by majority vote

In California, almost everything can be put to majority vote. Want to change tax rates? Put an initiative on the ballot. Don’t like the way the state government raised your taxes? Hmm… you can’t actually put that up for referendum, but you could achieve the same effect after the fact by initiative.

The “system” we currently have for changing the tax code in California could certainly be improved (I’ll get to that below), but even without that, this is would be great deal for California taxpayers. Total control over taxes, directly by the voters? This a deal you will literally never get from the federal government.

Can state government handle this?

On the other hand, if you’re not just a Californian taxpayer but someone who works on the state budget, this looks like it could be a huge headache.

Sure, when Trump & friends cut federal taxes, they’d essentially be giving California a huge block grant, but if the reverse ever happens, state revenues get slashed. Nice idea; do you even budget, bro?

Here a are a couple of reasons to worry less:

Stabilizing combined state and federal funding

Remember, the goal here is not to make the state budget bigger, or smaller, but to make changes at the federal level largely irrelevant to government spending in the state. If the federal government raises taxes, that’s probably going to result in at least some increase in spending on something the state wanted to do anyway (e.g. transportation), and we can focus our (reduced) state tax revenues on our other priorities.

The one major area of federal spending that wouldn’t help the State of California reach its policy goals is the military. However, historically, Congress hasn’t chosen to raise taxes to pay for wars, instead choosing to run up debt and figure it out later. Because war > fiscal responsibility > poor Americans? You’re asking the wrong guy.

Counterbalancing volatility in income tax revenue

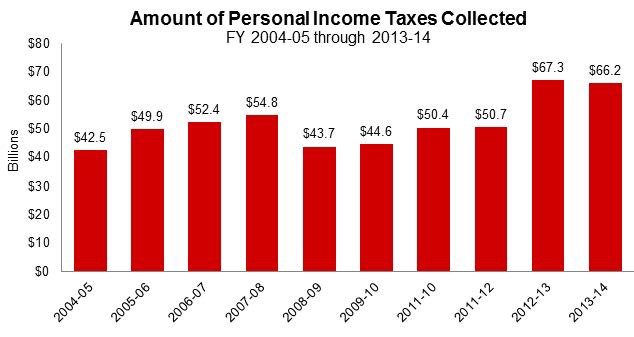

One of the problems with funding a state government from income tax is that it’s not very stable; when the economy is bad, income tax revenues are way, way bad.

This is probably mostly due to capital gains taxes; taxpayers who own investments tend to hold on to them during bad economic times, and hence no capital gains are realized until the economy is good again.

This turns out not to be a big problem for the federal government (which has basically unlimited power to borrow, and uses it), but for a state government which needs to balance its budget every year, this can be a big problem. (Protip: Rainy Day Fund)

The good news here is that the federal government rarely raises taxes during a recession (see: unlimited borrowing powers). Those state-revenue-busting federal tax increases would only come at time when income tax revenues are already high.

Money left on the table

There’s another huge reason for states to adopt a plan like this: federal tax expenditures.

Tax expenditures (also known as “loopholes” or “tax breaks”), are in essence, taxes that the federal government would have collected if the tax code treated all income the same, but that it chose not to, through tax credits or deductions, or more complicated things like depreciation rules. It’s not technically government spending, but it adds up the the same damn thing.

For example, did you know that the federal tax code now contains permanent favorable tax treatment for race tracks? That’s right; thanks to the federal tax code, NASCAR is, at least in part, a federal program.

Some tax breaks can be charitably viewed as incentive systems. For example, the Domestic Production Activities Deduction, is, in theory, supposed to keep manufacturing jobs in the U.S. (how is that going?). In practice, it works so poorly and costs so much in lost revenue that by 2013, 22 states, including California, stopped honoring it in their state tax code (it still exists in those states as a federal tax incentive).

If California enacted a scheme where Californians and businesses operating in California paid the same total amount of income taxes regardless of what the federal tax code says, then these federal tax expenditures would stop being incentives, and instead become merely a way for the federal government to dump tax dollars straight into the state treasury, no strings attached.

In other words, federal tax expenditures are money that the federal government is just leaving on the table, for any state to pick up.

A serious chunk of change

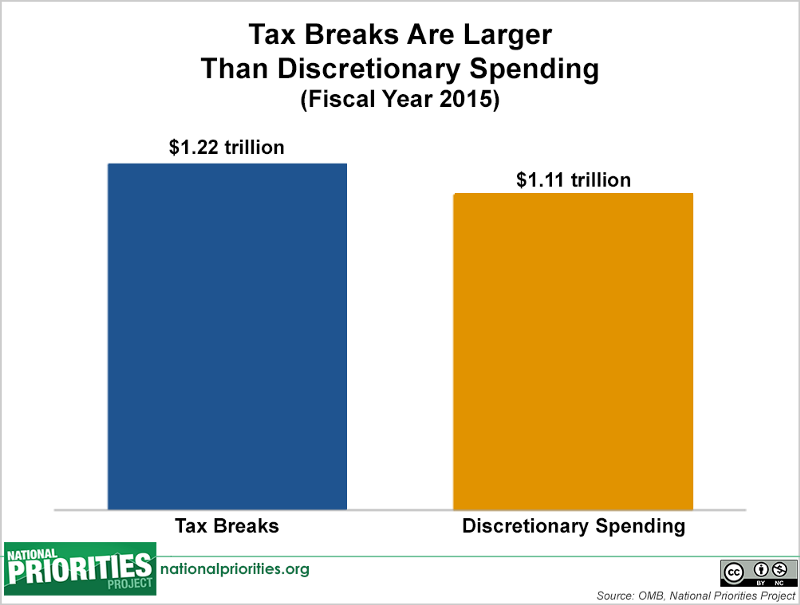

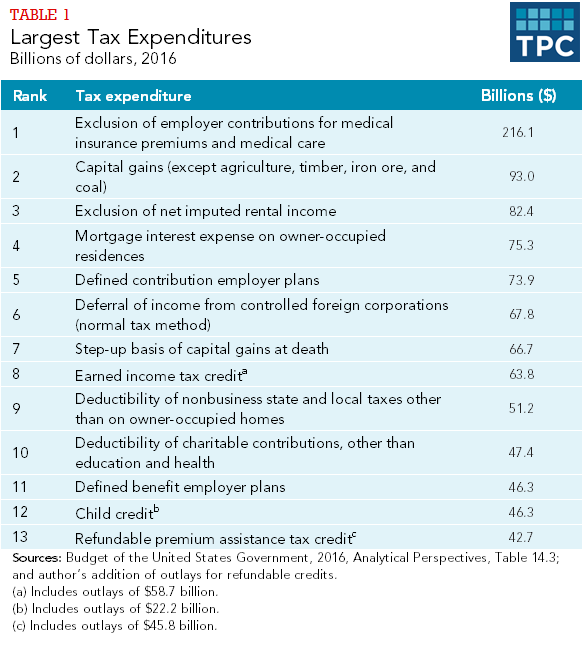

So? How much money are we really talking about here?

About 1.2 Trillion dollars a year, which is to say, a lot. Put in everyday terms, that’s about $15,000 a year for a family of four.

The National Priorities Project makes the point that this is actually larger than federal discretionary spending (the stuff that Congress decides on when it manages to pass budgets)

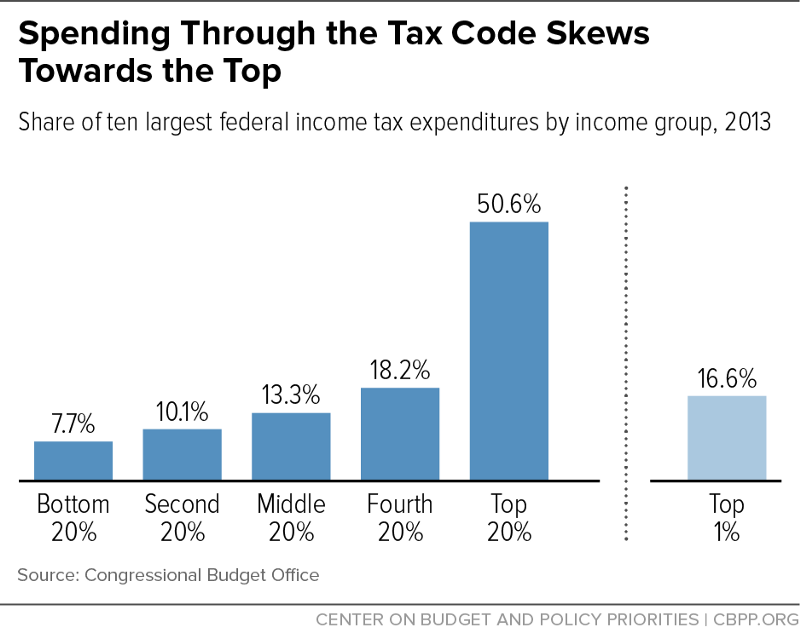

Another thing you should know about federal tax expenditures is that they disproportionately benefit high-income earners:

One of the things that’s so maddening about tax expenditures is that individually (the NASCAR thing aside), they often sound like a nice enough idea.

The key is to think of them in the context of government spending in general. Ask:

- if this were a federal program, would it be a good one?

- are there ways the money could be better spent?

Remember, we’re not just talking about letting people and businesses keep more of their own money. We’re talking about whether to have certain special rules that allow particular people to keep more of their money in particular situations. (Which is why it’s not so surprising that tax expenditures skew heavily toward the rich.)

How California could do better

The Tax Policy Center lists the largest federal tax expenditures. Let’s look at the top 5, and see if California could do better.

$216.1B/year for employer-provided health care

(about $2700/year for a family of four)

Why would we want to change this? Aren’t most employee benefits tax deductible?

Mostly because tying people’s health care to their jobs is a terrible idea. Why in the world should anyone with a serious health condition be put in the position of wanting to leave a bad job, but staying because they might get sick or die if they lose their insurance plan? This really only makes sense because we’re used to it.

The Affordable Care Act patched this somewhat by creating an individual market that anyone can access (though premiums are going up), and mandating business with 50 or more employees to provide health care coverage is a big part of how the ACA works.

However, imagine the ACA were repealed (or at least vandalized) by the current congress, or (more optimistically) if California were able to get a federal waiver. If California wanted to go its own way, perhaps moving towards a single-payer system, this money would be a down payment on funding it.

$93.0B for lower capital gains tax rates

(about $1200/year for a family of four)

The federal government taxes most capital gains (money earned as the result of selling stock and other investments) are taxed at a much lower rate than other kinds of income.

There’s an argument (which sounds especially reasonable if you’re wealthy) that capital gains need to be taxed at a lower rate, to incentivize investment.

Rather than wade into that argument, I’m going to point out that California has already decided which side it’s on. In California we refer to capital gains as “income” and tax it like everything else. (Interestingly, New Hampshireonly taxes capital gains and not other income. Take that, Laffer Curve!)

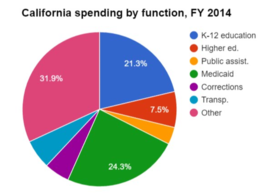

What to spend the money on? Honestly, just doing more of the same would be fine. Nearly 30% of California’s budget goes to education, for instance:

$82.4B for exclusion of net imputed rental income

(about $1000/year for a family of four)

This is more of a rhetorical point that the Tax Policy Center is making. If you rent, your rental payments are income for your landlord, but if you own, the government never sees the “rent” you would have paid to yourself.

Even if we were going to do this, it would look a lot like an ad valorem property tax on owner-occupied homes, and run afoul of Prop 13. Moving on.

$75.3B to deduct mortgage interest on owner-occupied residences

(about $950/year for a family of four)

This was created to incentivize home ownership, right?

Nope, this actually dates back to a time when people mostly paid for their homes in cash, and almost all interest payments were business expenses.

The mortgage income tax deduction is arguably a terribly “designed” programthat mostly benefits people who live in pricey homes. Plus (as a demand-side subsidy) it almost certainly raises the price of housing, which is not really what we want in California.

It’s also extremely popular, and part of the financial plan homeowners made when they took out a home loan. If we wanted to change this, the best way would be to start phasing it out for new home loans. And then, redirect that money to affordable housing or subsidized home loans for low-income Californians.

$73.9 for defined contribution employer plans

(about $900/year for a family of four)

4o1(k)s, basically. Not convinced this a bad idea. Maybe instead create a more robust Social Security system, with benefits that better match the cost of living in California?

Other taxes

Income taxes aren’t the only tax collected by both federal and state governments. Are there other taxes California (or any state) could take control of?

We should definitely do this for the estate tax and the gift tax (which basically exists to prevent getting around the estate tax). The estate tax is a frequent target of Republican Congresses; if California got to keep that money instead, I wouldn’t object.

On the other hand, payroll tax is probably a terrible fit for this approach. Not only are federal payroll taxes fairly stable and earmarked for Social Security and Medicare, but California doesn’t collect payroll tax directly from individuals at all. It’s not even handled by the same agency (EDD rather than the Franchise Tax Board).

It’s probably worth at least taking a look at federal excise taxes as well. For example, until 2011, ethanol subsidies (not a great fit for California’s diverse ag industry) were implemented as a credit against the federal gas tax.

An opportunity to fix a broken “system”

Hopefully at this point, I’ve convinced you that this is a basically solid idea, and California should go ahead with it. This plan is almost certainly going to need to be put before the voters. What should it include?

First of all, let’s take a look at the current “system” the state has for setting tax rates, that arose mostly as a result of Prop 13.

In California, the legislature can lower taxes by majority vote (assuming the governor doesn’t veto it). But if it wants to raise them again, it takes a 2/3 vote of each house, even if it’s a revenue-neutral change that only raises taxes on a handful of people.

On the other hand, it’s possible to make pretty much any change to the tax system by initiative (which requires petition signatures, a majority vote of the people, and zero votes from state legislators).

So far, so good? Californians don’t trust the legislature on taxes, but we trust ourselves. Fair enough.

What’s completely crazy and broken about this system is that if the legislature (that is, the folks whose job it is to write the state budget) want to ask voters if we’d like to raise our own taxes, that requires a 2/3 vote of the legislature too.

That’s why Prop 30, the income and sales tax increase to stabilize state government after the financial crisis, was an initiative. It definitely had the support of the governor and (the majority of) the legislature. It was just way, way more possible to collect signatures for an initiative than to convince a minority of legislators to vote for a tax increase.

If voters are already voting directly on major tax rate changes, and don’t trust the legislature to make these decisions, why not go all the way? That is, mandate that all changes to the tax code have to be approved by voters, but that the legislature can place proposed tax changes on the ballot by majority vote rather than 2/3.

We’d probably need to let the legislature retain the authority to make emergency changes to the tax code by 2/3 vote (much the way urgency legislation works now), but rather to these changes being permanent, we could force them to sunset after two years and/or the next chance voters get to have their say.

What to put before voters

In addition to giving Californian voters the final say on the tax code (and the legislature the ability to ask politely for changes), what else would we need to do to make this a reality?

Start with the status quo

Californians would likely be unimpressed at any attempt to squeeze just a bit more revenue out of the voters. The starting point is taking the current state and federal tax rates (and rules), adding them together, and making that the new tax code to put before voters.

On the other hand, it should be fine to give Californians the option to change tax rates at the same time; just present these options as separate ballot measures, and see which one gets the most votes. Treating all capital gains as ordinary income would probably pass. Or maybe make it like a walk down memory lane; would we prefer the combined average tax rates of the Obama administration? The Clinton years? The Reagan era? Carter? Eisenhower? Ah, nostalgia.

Fix the rainy day fund and spending formulas

Currently, the state’s rainy day fund keys off general fund revenues (i.e. state taxes). We’d need to update it to reflect the goal of stabilizing total state and federal spending. Including state-administered federal funds in the definition of “general fund revenues” might cover it.

We’d also need to update major spending formulas like Prop 98, which mandates a minimum level of education funding. We could use the same solution as with the rainy day fund, or stop tying it to state revenues at all and instead just track increases in personal income.

A cap on negative taxes

What happens if someone owes more to the federal government than California says they should pay in combined state and federal taxes? Using the power of subtraction, do they get to “pay” negative taxes, in effect getting a check from the state government? We do this now with the Earned Income Tax Credit, for instance.

The short answer is no; in the unlikely event that the federal government manages to raise someone’s taxes above what California thinks should be the combined level of state and federal taxation, they’re going to have to take it up with Congress.

The long answer is, in some cases, the fair thing to do is allow people to carry their negative tax bill forward as a credit against future taxes. There’s already (not to get too far into the weeds here) a mechanism like that for the Alternative Minimum tax.

If, for example, California wanted to make sure that poor (but lucky) tech workers weren’t prevented from exercising their stock options by a huge tax bill they couldn’t afford, it might even want to offer a tax refund, with the knowledge that California would usually get the money back later when the stock is sold.

This particular case would involve future changes to the tax code (which could be worked out at the time), but we might want a similar mechanism for business taxes.

Conclusions

At the moment, the biggest decisions about the size of government and its spending priorities are made at the federal level in the United States.

But this is only because states allow it; if any state wants to determine the total level of state and federal taxes its residents and businesses pay, or recapture federal tax expenditures for their own purposes, they clearly have the constitutional authority to do so, using only the powers of taxation and basic arithmetic.

The only recourse the federal government has is to raise taxes and spend the money directly, rather than through the tax code, which is, to put it mildly, politically unpopular.

This is a real thing we could actually do.

California, let’s declare fiscal independence!

This article originally appeared on California Rising.